AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From Charles Hartshorne’s Concept of God: Philosophical and Theological Responses, edi-ted by Santiago Sia, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1990, 269-279. Father W. Norris Clarke's critique is here.

Anthony Flood

May 22, 2010

Clarke’s Thomistic Critique

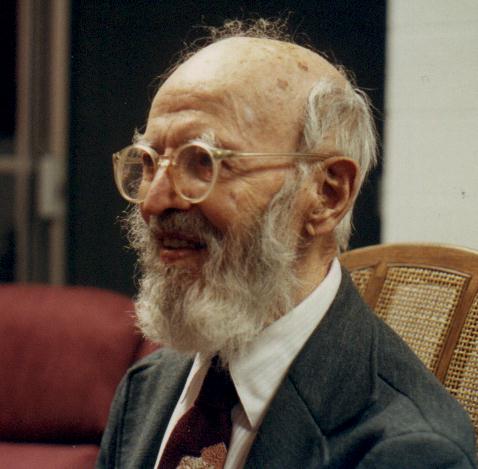

Charles Hartshorne

Fr. W. Norris Clarke honors me and Aquinas by taking us both, separated by seven centu-ries, so seriously. He thinks I do not do full justice to Thomas’s system. In this he is sure-ly right. To do full justice to any great thin-ker’s thought exceeds the power of human language; and certainly nothing like it can be done in anything less than a full book on the subject. I add, however, that Clarke has not done full justice to my system, hard though he has tried to do so.

In spite of my book title terming omnipo-tence a mistake, the discussions in the book qualify this charge somewhat. If the word means not-conceivably-surpassable or ideal-ly-great power over all, then I affirm this. No being other than God has ideal power over anything, and no other has power over all. In these two senses I agree with the tradition. Furthermore, I agree with the proposition that God can do anything the doing of which by an all-good and all-wise being is self-consistent. It is, however, contradictory to fully determine the free act of another. I have repeatedly said that these are the only limitations on what God can do. One belief that separates me widely from the medieval writers and early modern thinkers in this context is that, with Peirce, Whitehead, etc., I hold that every single creature (in contrast to collectives) has some freedom. Hence no portion of nature is fully determined by divine action.

As I have somewhere pointed out, “suffi-cient” reason or cause is ambiguous. It might mean, sufficient to make possible; it might mean sufficient to make actual. It is modal absurdity to identify these two. Without God, nothing is possible; indeed “without God” is nonsense or contradiction in my thinking (and this whether or not “with God” makes cohe-rent sense). I see only a rhetorical difference between what I say here and what Clarke wants me to say. Only with God, not merely with my nondivine predecessors, was I pos-sible—or was anything at all possible, even the pseudo-thing of sheer “nothing.” So I don’t see what beyond words is lacking. Divine po-wer is presupposed by any lesser power. Re-member that God is primordial and therefore, somewhat as every whole number is preceded by an odd number, so some divine state or other precedes any and every state of other powers. Divine essence-and-existence, as noncontingent, in unimaginably rich divine actuality (contingent in specifics), has always been there, no matter how far back we go.

I am glad my critic agrees with me that Thomas conceded, though Clarke is not sure he should have conceded, the logical possibi-lity of a beginningless past of the creative pro-cess. My objection to creation ex nihilo is that if God created me out of nothing, then our human idea of power lacks all basis in experience. Surely God used my parents, not just nothing. And, as Clarke notes, a first state of creation is paradoxical. An actual infinity is unimaginable by us, but there is no agreement that it is really contradictory.

Why are there other beings each additional to God as previously actual? There are plenty of reasons. To speak of ideal power is to imply the contrast with non-ideal power. The “prin-ciple of contrast” is axiomatic with me. Also, the notion of a supreme form of creativity cre-ating nothing seems an absurdity. Something is always better than sheer nothing. To im-pute to God the “ability” to do nothing seems to me no praise of deity. I have read Thomas and find his language taken at its best ambi-guous rather than clear, as to God’s power. The theologian James Ross has also read Thomas and interprets him as attributing to God power to deliberately bring about any conceivable state of affairs. True, Ross also holds, as I do, that eternally conceivable states of affairs are not fully definite. They are not possible worlds composed of fully definite individuals. From the standpoint of eternity, Ross said (in my presence) not even animal species can be identified. I agree. However (in his philosophy of religion book) Ross fell into the absurdity of solving the problem of evil by saying that if Shakespeare was not wicked in creating the extremely wicked Iago, then God was not wicked in creating, say, Hit-ler. As though Iago really did wicked things. Iago was an image of a wicked person, not a wicked person. If only Hitler had been but an image!

I have no adamant objection to saying that God is the ultimate “source” of all power. But words mean what we make them mean, “pay-ing them extra” (as the incomparable Lewis Carroll says) when we impart a somewhat new sense to them. I, too, say that we are images of deity, as, in dilute sense every creature is. Of course we participate in divine power. I have been aware though sometimes I forget—that Jesuits are not determinists, as Janzen and Pascal, Luther, and, I think, Augustine were. But if Thomas was trying to say what I say about freedom in relation to divine power, then I cannot think he did a good job at that point.

Clarke in one passage seems to imply as my view that a creature is, in its freedom, entirely self-caused. This only shows how difficult philosophy is. Plato said it first: what has soul is self-moved; but he failed to add what he must have known, that soul is also moved by others. Even knowing others is already that; one cannot know something if it is not there to be known.

Alas, there is more than a rhetorical dif-ference between Clarke and me concerning panentheism. I cannot possibly accept the idea that the cosmos adds numerical plurality but not quality or value, to the divine life. No-thing is more important to me theologically than our being able to genuinely “serve God” by increasing the aesthetic richness of the di-vine awareness. To call this a “limitation” in the divine perfection I take to be a definite mistake. As Whitehead saw, and Leibniz should have seen—since there are incom-possible values—no conceivable perfection could, in every dimension of value, be the greatest possible.

Why else should there be a world, if it adds no value to God? Nor does the mathe-matician-pupil example support Clarke’s point here. The mathematician may know all the mathematics the pupil can learn, or he may not know it; but in either case the pupil gives to the teacher the value which experiencing an interesting human being, unique in all history, can give. Similarly (although I incline to attribute to God complete mathematical knowledge without help from us) God is surely interested in, or enjoys, incomparably more beauty than that of mathematical ab-stractions. As for greatest possible or “ab-solute” beauty, that is a formula the meaning of which no one (Leibniz tried) has been able to tell us. I think the aesthetic dimension of value has no logically possible maximum. This still leaves an infinite, not a merely finite, gulf between us and deity; for God ideally enjoys all so-far-actualized aesthetic values in the present and preceding cosmic epochs. Long ago I distinguished between absolute perfec-tion, A, a real maximum, and relative perfec-tion, R, surpassing that of all actual others, and attributed both A and R to God.

Alas, again, I do not see clear logic in the workman analogy. The workman indeed uses the wood as mere means, but God enjoys us for our intrinsic values, our enjoyments, our aesthetic values. God also suffers in pre-hending our sufferings. In trying to show that this makes God and world so interdependent that all transcendence is lost, Clarke leaves me well behind, unimpressed, except that it reminds me again of how easily we are carried away by words. “Give a philosopher an inch,” wrote Peirce, “and he will take a million light years.” More simply, we (like politicians) are constantly exaggerating against each other.

As for freedom in the members of an or-ganism, I am reminded of my own frequent pronouncement: Show me a wrong view of God and I am likely to discover in it a wrong view of the basic example from experience to which God is being compared. In our bodies, I, of course, hold, there is no complete “or-ganicity.” If a cellular process somewhere in the body produces effects on such process elsewhere, this is not instantaneously, and there is no reverse action on the state of the previous process causing these effects. There is partial freedom and real distinction between cells. Whitehead takes the neural conditions of our sensations to be similarly prior, and any effects of the sensations will be on a later phase of neural process—later actual entities, in other words. Similar distinctions preserve the freedom of God and of creatures relative to each other. In short the view of organism used by the critic is for me a myth, and not in-cluded in my theory. I also reject the idea that “included in God” entails “identical with God,” and if it is said, “at least identical with a part of God,” then I say that “part” has several meanings. In knowing, the items known are parts of the knowing; but this is very different from a brick being part of a wall, or a finger part of a body. The subject-given-object inclusion is the most concrete form of inclusion; in the ideal case yielding to the sub-ject the entire intrinsic value of the given.

Plato said that the cosmic soul includes the cosmic body. I agree and fail to see that this spatializes the relation. On the contrary it is psychical ideas of relations that explain space. Prehension, intuitive inclusion, is, as White-head argues, the reply to Hume on causality. And space-time is the system of possible and actual causal relations. Of course subjects depend on objects. But for me, differing here from Whitehead, God is not a single subject in the most concrete sense; God is a person—that is, analogous to a personally ordered so-ciety of actual entities dominantly related to a nonpersonal society of subhuman actual entities.

Whitehead and I are entirely serious in taking prehension as “the most concrete form of relation.” I prehend the brain actualities more adequately than they prehend each other. But they do prehend my experiences in their deficient way. So I am in them as well as they in me, but I am, as a single subject or society, incomparably more dominant than anyone of them is. In God is the ideal form of all this, and it differs infinitely, not merely in degree, from the nonideal form. Plato saw (but the world partly missed the point) that the divine body differs from all others in the absolute sense that it has no external en-vironment. Plato drew some of the right con-clusions from this. We can draw some he could not, since he did not even know the function of the brain, or the mythical character of the notion of inert matter.

As Rabbi Kaufman tells me, long ago it was said that “the world is not the place of God, rather God is the place of the world.” How we are in God is the most concrete way to be in anything. Perhaps I may be forgiven for pointing out that to interpret the way we are in God (according to St. Paul) by the “field of God’s action,” to speak with Fr. Bracken, is to use a spatial metaphor. God prehends us, and this means that God’s actuality (not mere ex-istence) includes ours. I take as axiom that if for X to be without Y is logically impossible, then any description of X without mention of Y is incomplete. If God prehends us, then the di-vine actuality that does this prehending is in-completely described if we are left out. The metaphor “field” seems to me an inferior way to put the matter. If some prefer Bracken’s language, good luck to them. But how far are we arguing about more than words here? The substantive issues seem to me more on my side, or Whitehead’s.

Clarke is far from the first who has tried to get from the metaphysics of the Thirteenth to that of the Twentieth Century in a few small steps. If this is not possible, it is not only because much has happened between that time and ours. Scholasticism was, in my view, somewhat regressive in relation to the best thought in Plato, Aristotle, and Epicurus; and not only that, but also in relation to the best in the Old and New Testaments.

It is pleasant to read the commentator’s eloquent account of the divine sensitivity to all that passes in the world, and the great dif-ference the creatures make to the divine con-sciousness. So we are indeed far from Aris-totle’s doctrine of the unmoved mover—or from Pure Actuality—by any reasonable use of words. The contents of divine awareness must be contingently otherwise than they might have been. This means that divine po-tentiality is as real as divine actuality. So why the “pure?” I have taken that literally. So did Spinoza, to whom it meant, no contingency.

I have read Augustine on time (seventy years ago) but was not convinced by him, though I did agree with him that time makes no sense apart from mind, the psychical. But I also agreed with Hume long ago that a purely timeless mode of experiencing is “language idling”—to borrow a phrase from Wittgenstein. With Aristotle I agree heartily that “eternal” entails “necessary,” and “contingent” entails “not eternal.” Accidents happen not in eter-nity but in some analogue to what we call time—if you like, in the unsurpassable form of “existential time” (Berdyaev). One could give a long list of writers (including Karl Barth) who have struggled with the idea of all time being included in or known by something unchanging and have concluded that it lacks coherent sense. It spatializes time (Bergson, preceded by Lequier in different words); space being the symmetrical or directionless, and time the asymmetrical or directional, order of depen-dence and independence.

I wonder if, at this point, I am not more Thomistic than Clarke. For the great Medieval scholastic (as I, and not only I, read him) contingency, potentiality, and change belong together. The Socinians dealt carefully, know-ing what they were doing, with this problem and came to the same conclusion as Bergson or Whitehead. So did my teacher W. E. Hoc-king, who convinced me on the point before I knew the other thinkers just named. Many things could be said against the idea of all time as a completed whole. I am as surprised by Clarke’s idea that there is no hopeless difficulty but only mystery in this, as he is by my position. Just take one point. If we now are right in saying that God knows all tomor-row’s happenings as definite items, then it is now and not merely eternally true that this is so. I argue, as the Socinians did, that there can be truth about tomorrow’s happenings only when there are such things as tomorrow’s happenings. And if there eternally are these things, then everything is as eternal as God.

I take the merely eternal to be what all times and changes have in common, and dis-tinguish divine everlastingness: and primor-diality, or unndying and unborn existence, plus uniquely adequate retention of value or actu-ality once achieved, both from the merely eternal and from our way of being temporal—infinitely different as that also is. To assert timelessness of God’s full actuality adds only a negation, and one that seems to cancel out concreteness altogether. It is abstract truths that can be timeless, like those of arithmetic. “Highest degree of intensity perfection” as-sumes that this phrase describes something conceivable positively without contradiction. How do we know this? I incline to think we face an open infinity here with no highest de-gree possible.

Does God have a rich inner life? I certainly think so. But note that I take even our inner life to consist not only in our perceptions of others but in our present memories of our own past experiences—not just their data but themselves. Introspection is not timeless, but (as Ryle says, and also Peirce and Whitehead as I read them) is a form or use of memory. Experiences prehend not themselves but their predecessors; some of these predecessors are one’s own past states, that is to say: mem-bers of one’s own “personally-ordered” soci-ety. Thus with new creatures there are new divine subjects intuiting, enjoying, their pre-decessors. There is no need for each new ac-tual entity (divine or not) to prehend itself, it is itself with all its value.

Remember, too, that God enjoys not only all of our cosmic epoch but an infinity of others that in divine time preceded them (somewhat as in Origen’s view). So our inner life is almost nothing compared to God’s as aware not only of all past objects of divine prehensions but of all past divine prehensions of these objects. This is a, to us, unimaginably vast fullness of experience. Again, how substantive rather than verbal are our disagreements?

Here is another difference that I cannot in-terpret as Clarke does. I deny absolutely the notion that the unqualifiedly simple can em-brace or possess anything complex. What is consistent is to say that the simple can be embraced by an actuality that is complex. (XY includes X.) The divine simplicity, like the divine, eternal and necessarily existent es-sence, is an abstraction that is divinely, as well as humanly, prehended and so, in the most concrete sense of inherence, is in the di-vine consciousness—which is the most com-plex of all actualities. This complexity is ideal-ly integrated and reintegrated with each new divine prehension. The divine personal order is not interrupted by dreamless sleep, insa-nity, multiple personality, as ours is. Nor are its intuitions indistinct as to particulars and inadequately preservative of vividness.

Not only are the contents of God’s worldly prehensions finite and contingent, so are the already actualized of these prehensions as subsequently divinely prehended. Knowledge of the finite cannot be simply infinite, just as knowledge of the contingent cannot be simply necessary. As the Greeks suspected, the finite is not less than the infinite but more, for only the definite, this rather than that, has beauty in the primary sense. Clarke does not mention the mistake I see in taking finitude as the mark of our inferiority in principle to God. Fragmentariness, being but a part of the finite, is the mark. God is non-fragmentary; his is the all-embracing finitude. This is incompa-rably more than the merely infinite. Similarly, divine relativity is the inclusive divine attri-bute, not absoluteness. The Hindu Sri Jiva Goswami, or one of his followers in the Hindu Bengali school, virtually said this long before I was born.

Sorry, I am aware of but reject the doctrine of intentionality as in Thomism. According to it, God knows the world because of the divine self-knowledge: the divine essence is cause of all things and in knowing the cause one knows all its possible effects. Yes, but possibility is incomparably less rich in definiteness than ac-tuality. Ross, mentioned above, seems to know this; how it fits into his view of Thomas I do not know. To unqualifiedly know something is to possess it in all its qualities or values. Most of our knowledge is intentional only, and not possessive. That is how we are not divine. Husserl went badly wrong here, blurring the distinction between having as given and merely intending what may or may not be. When we (or anyone) prehend, the prehended must be; however, all nondivine prehension is indistinct, excludes most details from definite awareness. Only God can see that they are there even in us. The indistinctness is a Leib-nizian doctrine, but his “no windows” means, no prehensions except those whose data are one’s own past states.

If the past of creation is beginningless, then, although the divine actuality, like all ac-tuality, has a certain finitude, it is not in all di-mensions finite. But neither is it in all dimen-sions, or absolutely, infinite. It is not the ac-tualization of all possible value. Each moment free creaturely (and divine) choices exclude forever values that the creatures, and a for-tiori God prehending the creatures, could have had.

No less than Bertrand Russell agreed with me that the following is logically possible: Nu-merically there are, in the objectively immor-tal past, an infinity of achieved actualities; yet each moment there are additional actualities. Nothing has been taken away, something has been added. There must, in some sense, be more. Aesthetic richness need not mean the same as classification as to order of multi-plicity. Each new state of the world is felt by God in contrast to all values already pos-sessed. I find no benefit in giving up the idea that we increase the divine beauty or joy com-parable to that of keeping the idea.

The reason I have not emphasized terms like “source,” for the divine preeminence is that historically they went with underempha-sis upon certain other terms. Causation is not handing out something already there; it is always creative and always receptive of past creativity—above all, divine creativity. The truly absolute infinity of the divine potentiality for value distinguishes deity from humanity by a more than finite difference, yet all actuality is, by definition, finite in some way. To be finite is to leave unactualized some of the absolute infinity of possibilities. The point of actualization is the gain in definiteness. Spino-za tried to make God wholly, or “absolutely” and in actuality, infinite and therefore denied contingency: his God is and has all that God could be or have. By admitting contingency in God, Clarke compromises his denial of change and finitude to God.

Clarke talks about “activities” in the Trinity without enabling me to see any reason why they could occur with no analogy to time. It is time that provides a real distinction between what might have been and what is, or what may yet be and what is. To say that God does X and might have done (note the words) something else instead implies, as Spinoza says, that we can conceive God as first not having done X and then as doing X. As Peirce says, time is “objective modality.” “Without time yet with modality” is a leap in the dark. I see no worse paradoxes in my view than in the Thomists’. And the new paradoxes may turn out to be more soluble than the older ones. (For instance, the Trinitarian “circula-tion,” “giving and receiving,” in mere eter-nity.)

That my view is not free from paradoxes as it now stands, I grant. Bell’s Theorem in quan-tum physics may perhaps not help. I know too little of physics to be confident in such topics. As my first teacher in philosophy, Rufus Jones of Haverford, said, “There is an impasse in every system somewhere.” Whitehead says similar things. If there were no difficulty in our understanding of God, it would not be God we were understanding. But when I compare my opportunities to think adequately with those of any Thirteenth century writer, especially one with so short a life as Thomas’s, I think I must be stupid if I have done no better than he. Considering my childhood and youthful ex-periences of a very intelligent and highly-trained father, the seventy years and more that I’ve been thinking about the theistic prob-lem, the many teachers of distinction I have had, the resources in comparative religion and comparative philosophy, and so on, it seems clear I have had many advantages. Therefore, with great assistance from many, including Clarke with his stimulating essay, I just may have gone farther than he quite sees in the process of improving upon classical theism. Improvements are sometimes painful; new linguistic habits come less easily with age. My father had a teacher, and I had many tea-chers, who deliberately broke with classical theism. I did not have to unlearn thinking in that way. I did have several Thomistic tea-chers here and abroad. And some of my most enthusiastic pupils or readers have had such teachers.

As I said in the beginning, I feel honored by the serious, and I now add the generous, way Fr. Clarke compares two forms of philosophical theology. Old as I am, my linguistic habits should, and perhaps, will change some, thanks to his essay.

Since writing the foregoing paragraph I have indeed acquired a new linguistic habit or two which I believe will constitute a marked improvement or addition. I thank Norris Clarke for this.

The medieval synthesis bequeathed to us a number of extreme, and as they stand unintel-ligible, dualisms, mitigated somewhat by hints that and how they can be reduced to mo-derate, more intelligible dualities. For a dual-ity on the most general level to be intelligible, one pole of the contrast must furnish the posi-tive explanation of the other. It must include or possess it in a more than spatial sense. (That “in” or inclusion is not exclusively spa-tial is shown by the truth that minutes are in hours as truly as inches are in feet! Also a multitude of 3 includes one of 2. Inclusion, in its reasonable general meaning, is far from a mere spatial or temporal metaphor.)

Among the medieval dualisms, not intelligi-ble as they stand, are: mind and (mere) mat-ter or subject and (mere) object; dependent and (entirely) independent; relative and (enti-rely, exclusively) absolute; soul and body or psyche and soma; value-maximal and nonma-ximal (surpassable—by self? others? both?). Medieval hints as to how to reduce these unintelligibly extreme to legitimate dualities include the following. The Scholastics agreed with Aristotle that in all other cases knowing depends on the known, they should not have said the opposite about divine knowing. In-deed, it is clearer that infallible knowing must correspond or conform to the known than that what is called knowledge in us must do so. Since, then, God knows all things, God must in some way depend on all things, whereas we, knowing far from all things need not (and in-deed cannot) depend in any such way on all things. God must have an infinitely excellent form of dependence as well as an infinitely ex-cellent form of independence. Moreover, what God knows must in some genuine sense be in the divine knowledge, which must in some ge-nuine sense be in God. We should recall what the Scholastics forgot or never knew, Plato’s double proposition that bodies are in souls more truly than souls in bodies, and that the divine or cosmic soul contains and possesses its cosmic body. Also the mind-body’ relation in this case is obviously a one-many relation, and there are many souls in the cosmic body. Taking into account the cellular-molecular-atomic-particle structure now known of animal bodies, Plato’s theological analogy becomes more definitely relevant than it could be in an-cient times. We should also recall the me-dieval doctrine of transcendentals, or super-categorial ideas which apply to God as well as to all creatures. The neoclassical form of this doctrine is that the difference between the es-sential divine attributes and the universal creaturely categories is that the latter are the by-others-surpassable and the former the not-by-others-surpassable forms of know-ledge, love, power, goodness, and the like. Di-minish the divine attributes to allow for this difference in principle, not merely in degree, and you have what all singular creatures have in degree above zero. Bonaventure seems to hint at this more than other Scholastics, and some renaissance thinkers (Campanella, Car-danus) make the principle more explicit. God is eminently powerful, knowing, loving; even the least creature has in some degree all of these qualities or capacities.

Leibniz achieved a partial further clarifica-tion by reducing, in minimal cases, knowledge or love to simple sensings or feelings (petites perceptions or sentiments). In this way the material or physical is the class of most primi-tive and widely distributed forms of the psy-chical; and the mind-body relation is a relation between two or more levels of mind; it is a mind-mind relation, and in principle intelligi-ble. This can, as I argued in an essay on “A World of Organisms,” enable us to generalize beyond hylomorphism to psychoticism, and this to a transcendental such that even God is psycho-somatic, and not simply “disem-bodied” mind or spirit.

It seems odd that it could be thought that deity might be incarnate in a single animal (a single human being) named Jesus but not in the cosmos as super-animal, as Plato implies in the Timaeus. The duality wave-particle can, in principle, I surmise, be treated as one as-pect of the psycho-somatic duality without implying anything like the stark dualism of Descartes’ inextended but thinking substance or process and extended but not even sensing or feeling substance or process. Quantum physics in this aspect concerns processes so minute and rapid spatio-temporally as to be radically inaccessible to mere common sense.

I have shown elaborately in various wri-tings that being absolute does not exclude be-ing temporal, if absolute means independent. I am strictly independent of my remote des-cendants (if there ever are any) but they must be dependent on me for their existence—which does not mean that they will have no genuine freedom. On the contrary, if I strictly depended on their future existence and ac-tions, then they would have no freedom. De-terminism destroys freedom in both temporal directions. “Necessary and sufficient condi-tion” as classically used is a symmetrical for-mula, meaning necessity in both directions. That is enough to condemn it as a literal truth. Hence I am unimpressed by Clarke’s emphasis on the latter part of the formula. Leibniz’s principle is too strong and excludes freedom, as Crusius wrote long ago. Kant, who reported this (causing me to look it up in Crusius), failed to see the point and hence had to resort to the absurdity of a wholly noumenal, time-less freedom for his ethics. How absurd it is was shown by his admission: “we do not even know that there are many rather than only one noumenon.”

The moderate dualities appear in the way creatures, too, have some strict absoluteness (or independence) of successors born after their death and (apart from some extremely subtle, limited, and practically irrelevant, quantum phenomena) even of remote con-temporaries, whereas all creatures depend for their very existence on their predecessors. On the contrary, God does not depend for very existence upon any definite existent or set of existents, but does depend for some contin-gent qualities upon every past existent in this and all so-far actualized cosmic epochs, and will depend for some future contingent divine qualities upon every creature that ever comes to exist, from none of which (if it comes to be after our deaths) will you or I get anything at all. Thus the ways we differ from God both in our absoluteness and in our relativity are more than differences of degree, they are differences in kind, infinite differences. So to the charge that I diminish divine transcen-dence I cannot respond otherwise than by saying that I think I make deity more intelli-gibly transcendent than classical theism or pantheism do. The “logic of ultimate con-trasts” is the key.

By admitting contingent divine qualities and intrinsic relations to the world, Clarke opens the door to this logic, then tries to close it with reference to change. The neoclassical view affirms of God not just any kind of change but change only in the form of increase in aes-thetic enrichment. To exclude this seems to me arbitrary logically, though it may seem un-shocking because there is so much precedent for it. But I can cite many precedents on my side, both Greek and Biblical, and much sup-port from changes in science since the Middle Ages. We now know how deep into reality becoming, or coming to be, goes. All natural science now is a kind of natural history. And many theologians imply and some clearly state something like a divine history.

Niebuhr spoke of “beyond history” but his approval (in print and conversation) of my view was too cordial to harmonize easily with the notion that he meant more than worldly history in the quoted phrase. Nor did he re-ject, although he stopped short of accepting, my view, which is Whitehead’s, of objective immortality as sufficient overcoming of death. He preferred, he said, to leave the matter open, or a “mystery.”

It is those who claim to know about our survival in other than divinely objective form that I wish to challenge. Also, those who insist that the survival must be forever. I deny that they can know this, and wonder if it makes sense. “Forever” is easy to say, but not so easy to really think, and it is difficult enough to justify thinking it of God without re-quiring believers to think it of themselves or ourselves. It is time now to stand by theism without adding all sorts of other ways of tran-scending what science can definitely test for its truth. My religion is belief in God and our ability to love God; the rest follows from that. I love myself and my friends, relatives, and readers as finite, nay fragmentary, spatio-temporally, apart from God’s weaving all that we are between birth and death into imperish-able wholes, everlasting but not timeless, in the everlasting but not timeless divine expe-rience.

That divine temporality and worldly tempo-rality (as grasped in my feeble understanding of physics, a science undergoing considerable change and expectations of more change) are not easily combined seems to me a serious but not a decisive objection. To understand deity without diminishing it to our level may not be any less difficult than this particular problem suggests it is.

For many years I have been aware of Fr. Clarke’s critical comments on neoclassical theism and find it fitting that I have been at last put in the position of having to reply to them. In these difficult matters disagreement need not be looked upon as lack of respect. To judge from the account given of it by Frederick Ferre in his Philosophy of Technology (Engle-wood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice Hall, 1988), Profes-sor Clarke’s essay ‘‘Technology and Man” (see Mitcham and Mackey, eds., Philosophy and Technology, N.Y.: The Free Press, 1972) is a valuable contribution to our thought about its subject. [This is a slightly revised version of Clarke’s, “Technology and Man: A Christian Vision,” Technology and Culture, Vol. 3, No. 4, Proceedings of the Encyclopaedia Britannica Conference on the Technological Order (Autumn, 1962), pp. 422-442.—A.F.]