AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

Murray N. Rothbard

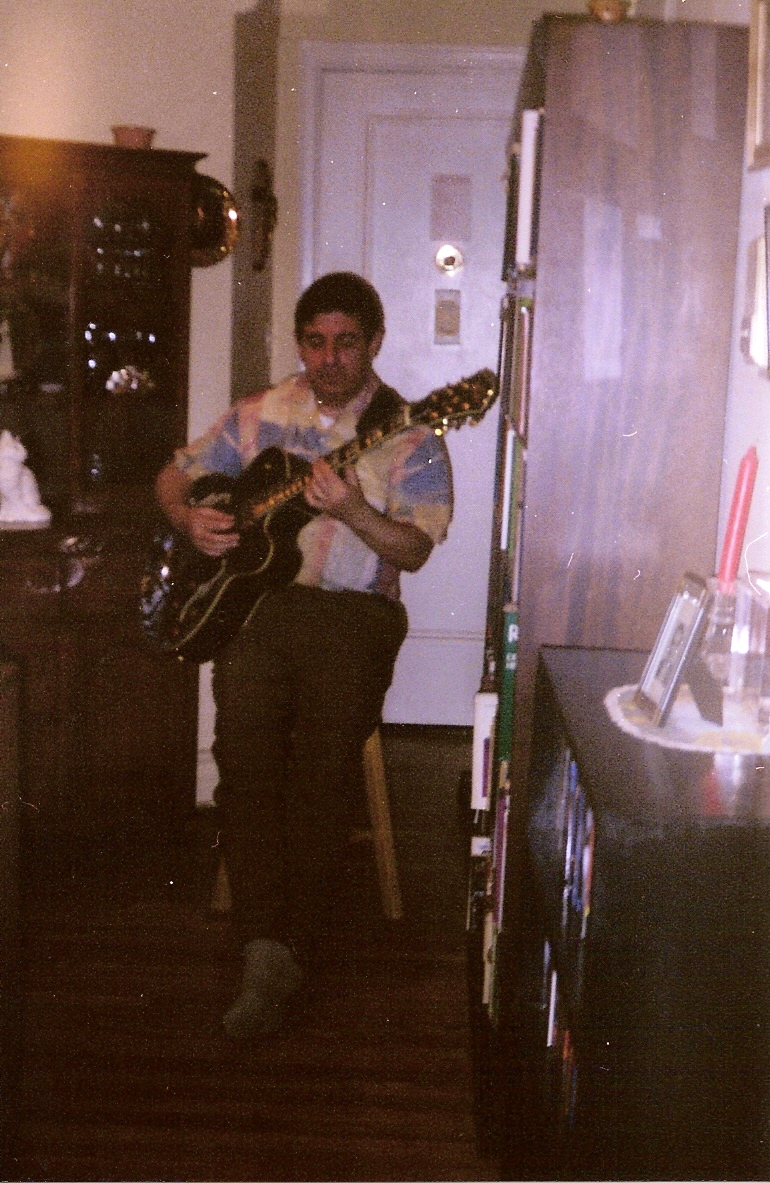

Tony Flood who, at least in regard to jazz guitar, is certainly an unregenerate seeker.

More than one visitor has expressed interest in reading my letter to which Murray Rothbard’s was a reply. For the record, and only for that purpose, it is reproduced here and followed by my reply to his letter. I was not fortunate enough to receive another written reply, but our conversations continued over the next decade by phone and over lunch in his New York City neighborhood during his summer breaks from teaching at the University of Nevada.

These letters mark a phase of a journey. If they occasion laughter, even derision, in the hearts of my fellow Rothbardians, that’s fine with me. They should consider that through all the ups and downs of that ongoing journey, it is my Rothbardianism that has survived, not the idealism, not the utilitarianism, not the classical theism. And all should bear in mind that while are many ways to find out what I now believe, perusing these letters is probably the least reliable among them.

Anthony Flood

August 20, 2007

Letters to Murray, 1984

Anthony Flood

July 6, 1984

Dr. Murray N. Rothbard

5 Pearce Mitchell Place

Stanford, CA 94305

Dear Dr. Rothbard,

It’s hard to believe two months have passed since we’ve last talked. Perhaps another twelve will go by before we do so again, I regret to note. I hope you and Mrs. Rothbard are enjoying your summer home. Gloria and I are well settled into our new apartment and are looking forward to a few months of Sundays in Central Park, Lincoln Center and the like, and maybe a week in August away somewhere. Since philosophic communication is easier in a letter than at a bus stop,1 writing to you is the one consolation of your absence.

About a week after your last class, just when I thought I had reached bedrock with your system of liberty and looked forward to rendering more compact your Man, Economy & State, I came upon one of the works of the mystic Alan Watts, Beyond Theology. For the first time in my sixteen years of reading philosophy, Buddhism became at least intelligible, if not attractive, and all of May found me devouring seven more of Watts’ books. Watts, who once served the Anglican communion as a priest, exposed the many biases Western theology students such as myself bring to their study of Eastern philosophy. And most unexpectedly, Watts has reawakened my interest in philosophical idealism—between which and Buddhism I have found not a few parallels—an interest which threatens to dismantle the neo-Thomist realism I have built up over the last six years.

The relevance of this to our common interest in libertarianism is that my revivified idealism has shaken my confidence in the natural rights approach to liberty and individualism I learned from your writings. I continue to accept your argument for the possibility of a stateless economy and your institutional analysis of the State. But to me that is not enough for a libertarian challenge to the ethos of statism. In an early draft of this letter I began to present my alternative philosophic foundation, which at the moment consists of a coherence theory of truth, a critique of metaphysical individualism and of the derivative doctrine of the ego, and—this is the hard part—a part mystical, part utilitarian critique of morality. I am convinced that nothing compels or repels as does perceived utility, and into this kind of talk virtually all moral discourse can be translated. What such a transposition will most require is universality or systematicity, being the main attraction, to my mind, of naturalistic theories of morality: I want to know what “utility maximizers” must realize in order to systematically avoid aggressing against each other.

My tentative position is that the realization in question is the Self-knowledge of which mystical philosophy speaks. If the metaphysical distinction between persons, and indeed, between any two things, is not absolute, then every person is identical with the whole of reality and distinguished only by the awareness that the whole achieves at each personal “node.” All personal relations in this scheme of things are cases of Self-relation. All aggression consequently becomes Self-violation and a disutility for each personal node of the Absolute Self. Since all these ideas require arguments—without which you may fairly conclude that I have flipped my lid—I found my treatise growing inordinately long and thought it better not to delay the letter any longer. Thus I send this shorter version to you, promising to submit my fuller treatment of the issues when I have figured out how I will provide it.

If there is any caution you think I should take as I do this philosophical mining, please do not hesitate to share it with me. What I learn most from thinkers such as yourself is not particular positions, but the reasonable temper that is the surest guide in rooting out error.

Looking forward to hearing from you soon, I am

Yours for liberty,

Tony Flood

* * *

Murray Rothbard's letter to me of August 11, 1984

* * *

August 24, 1984

Dr. Murray N. Rothbard

5 Pearce Mitchell Place

Stanford, CA 94305

Dear Murray,2

It was a relief to receive at last your letter of August 11: I was ready to send out flares. I didn’t mind the lapse of time as much as wondering if I had your correct address. I will suffer similar pangs of uncertainty until I hear from you from your Nevada estate.

A skeptical challenge tempered by friendship and respect was all I wanted from you, and you did not let me down. What you call “gibberish” is my alternative to the deceptive sobriety of your materialism. It indeed has, as I wrote, “not a few parallels” with Buddhism, but is by no means identical with it, and even less so with the products of the fried-brain crowd you seem to encounter in your California treks.

Please note that Alan Watts reawakened a dormant interest in F. H. Bradley’s idealism (even though Watts never mentions Bradley), an interest side-tracked for five years by hopes for a very conservative brand of Christian theology. Reading Watts sparked a search for a philosophical framework to replace the classical theism that has ceased to inspire me. In this letter I will limit myself to outlining the compatibility of what must seem most incompatible: absolute idealistic metaphysics, with its doctrine of the one true self, and a “rule-utilitarian” libertarianism, which is true for all persons independently of the degree of their grasp of their true identity.

It is possible to bring a metaphysical egoist to libertarianism without any recourse to objectivistic rights. All he need understand is praxeology and its consequent “rule-utilitarian” libertarianism: the observance of the rules of liberty (the self’s ownership of its body; homesteading; voluntary exchange) make members of a libertarian society better off than they would be without their observance. They would be better off, that is, with respect to their overall individual peaceful pursuits of happiness, not necessarily with respect to the peaceful pursuit of any particular utility. Arguments for “natural rights” cannot add one iota of cogency to the praxeological proofs of the universal harmony of interests on the free market.

But metaphysical egoism’s world of mutual strangers is ever forestalling a war of all against all, because each ego is a potential threat to the security of each unknown, externally related other. As Hobbes taught, people will sacrifice whatever degree of liberty is necessary to avoid violent death: egoistic fear of neighbor toward neighbor is the mainstay of statism. There have, of course, been absolute idealists who have gone beyond defending their philosophical concept of a public realm of right called the “state” toward an apologia for existing states, but the thrust of that concept has ever been a defense of individual freedom through self-knowledge. Such knowledge is complemented by praxeological theory and its libertarian implications. There is a range of approaches to libertarian propaganda, from one assuming little self-knowledge on the part of the potential convert, to one addressed to more enlightened souls. The degree of self-knowledge is a “variable” coordinate with the “constants” of praxeology.

I incline to the platonic view that the problem of evil is not so much that of a bad will but of ignorance, which in the end is self-ignorance. By refuting “pragmatic” resistance to total liberty, praxeology overcomes one kind of ignorance. But the valuation of liberty’s (second-order) utility as the set of rules best facilitating the pursuit of other (first-order) utilities is a rather abstract proposition, which by itself is not robust enough to subdue the urge to gain a satisfaction through aggression. What is needed is a deliberate, principled adherence to the rule of non-aggression. This ethical policy is a function neither of the suspension of time-preference nor of the intuition of occult “natural rights” but rather of the direct perception, however dim and distracted, that one’s potential victim is in some sense identical with oneself.

Ethical performance, therefore, is as much utility-maximization, the pursuit of “enlightened self-interest,” as any other human action. The greater one’s enlightenment as to who the self really is, the more the limits assumed by metaphysical egoism are transcended, and therefore the more likely one is to find the commission of aggression repugnant. A society comprised entirely of enlightened individuals would manifest the laws of praxeology, but the self-conception of its utility-maximizing members would outlaw in their hearts the very thought of aggression. To the degree that this perception of identity is absent, to that degree unethical behavior will be unleashed. Nothing intellectually inhibits that perception as does metaphysical egoism; nothing reinforces it as does absolute idealism.

Father Toohey’s suspicion of capital letters would ironically apply to his own references to God and to himself as “I.” No doubt excessive capitalization can be self-defeating, but I fail to see how I offend in this way. You yourself have proven the effectiveness of capitalizing “State” while avoiding the danger of treating its referent as a concrete entity. I do not need to capitalize “self,” but it is convenient to do so when referring to the absolute self of which finite personal selves are emanations.

Al though your friendly ridicule is a small price to pay for your audience, I hope you take your “Cosmic Toe-nail” retort less seriously than the space you gave it suggests. In my letter I argued that if the metaphysical distinction between persons is not absolute, then every person is identical with the whole of reality and distinguished only by the awareness that the whole has achieved at that particular point of focus. If no distinction is absolute, then all distinctions are relative, in which case reality is one unbroken whole, any of whose parts is but a focal point or “node.” The real identity of personal nodes (actually of the emanating Self “behind” them) is knowable by them, and when known, makes interpersonal aggression virtually impossible on the basis of simple, clearly perceived Self-interest. To refute me, you need only give me an example of a real “absolute distinction” (not one that holds between abstract concepts), or show me that the relativity of all distinctions does not imply that reality is one unbroken whole.

There are just a few more comments. Until I find copies of the Cohn and Kolakowski books, I will remain in suspense about their bearing on our discussion. Your distinction between finders and seekers, I mean, Finders and Seekers, is intriguing, but why your implied negative regard for Seekers? I do not see “seven years of Buddhism” ahead of me. My desire for a world of unhampered markets with its benefits to mankind is as real as my desire for self-understanding and peace. What I am sharing with you is my attempt to integrate these goals. Surely we are not so close to the libertarian goal that my “anarchristian” speculations are simply uncalled for.

Hoping you have enjoyed your summer at Stanford, that this letter reaches you before your move to Nevada, and that I will get your devastating criticism of these few pages very soon, I am

Your Unregenerate Seeker,

Tony

1 After sessions of his Seminar on the History of Economic Thought, I would wait with him for his uptown bus (from New York University to the Upper West Side), often deciding to ride with him. It was during those talks that we got to know each other.

2 I took his signing of his letter with just “Murray” as the go-ahead for addressing him with such familiarity, although that did not come easy for this product of a Jesuit military high school education. I later saw how important it was to him that the younger people who were excited about his writings connect with him, and so how quickly he would correct any well-intentioned youngster who began his remark or question with “Dr. Rothbard . . .”