AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

.jpg)

The American Historical Review, Vol. 101, No. 1, February 1996, 304-305. Exactly six years later, Murray had another, longer letter on Scottsboro in the same journal, posted elsewhere on this site.

“If Goodman had been an ‘old-fashioned’ historian, in his introduction he would have had to refute explicitly the feminist lie, so popular during the Clarence Thomas hearings, that ‘women do not make up stories.’”

Posted May 27, 2008

Hugh Murray

To the Editor:

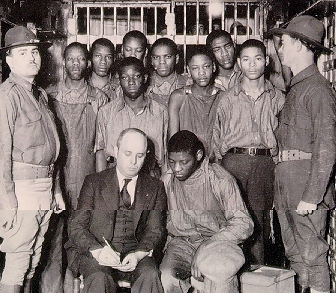

In his review of James Goodman’s Stories of Scottsboro (AHR, 100 [October 1995]: 1322), Robert P. Ingalls writes, “The significance of Goodman’s contribution transcends the Scottsboro case. His deliberate ‘experimentation in the writing of history’ is enormously successful in creating a form that does ‘justice to the richness and irresistible power of the past.’’’ I thoroughly disagree; the one thing Goodman notably fails to accomplish is justice to the past, or to the present.

Bluntly, if present-day rape-shield laws had been in effect in Alabama in the 1930s, not only would the Scottsboro boys have been executed, the “shielded” testimony would have proved their guilt!

It was only through the Communist-led International Labor Defense (ILD) that the boys’ lives were saved and the case appealed to the Supreme Court twice for precedent-making decisions. Again, it was the ILD’s attorneys and publicity campaign that exposed to the general public the intense racism in the Alabama judicial system and that the semen found in the two white women had come from their white boyfriends, with whom they had journeyed from Chattanooga as hoboes on a freight train.

Furthermore, Judge James E. Horton knew the boys were innocent, for Dr. Marvin Lynch told the judge in private what had occurred. The doctor was called to examine the women who had each just been “raped” by six young blacks, who had threatened the women at knife point and with a gun. Dr. Lynch was shocked to find the women giggling. He asked them directly, “Those boys didn’t rape you, did they?” The women laughed. Goodman finds this crucial story so inconsequential that he fails to mention the doctor’s first name and places the story out of chronological order.

If Goodman had been an “old-fashioned” historian, in his introduction he would have had to refute explicitly the feminist lie, so popular during the Clarence Thomas hearings, that “women do not make up stories.” With an introduction, Goodman would have had to question if justice could have been obtained at Scottsboro under feminist rape-shield laws. Goodman would have had to note that the run-off primary in Alabama, far from being the “racist” gimmick alleged by Jesse Jackson and the Justice Department under both Presidents George Bush and Bill Clinton, had originally been enacted to make it more difficult for members of the Ku Klux Klan to win elections.

Had Goodman been an old-fashioned historian, he would have had to give more credit to the Communists, who, with their international connections, made the nation and the world aware of racial injustice in the South. Thus, when Communists stoned American embassies and consulates in Berlin and Dresden, demanding freedom for the Scottsboro boys, President Herbert Hoover’s State Department had to inquire about the case. Before Scottsboro, how many southern rape cases were discussed in the White House? The Communists led Scottsboro protests from South Africa to China, from Ghana to France. They even organized a Scottsboro-civil rights march on Washington in 1933 (three decades before a much larger march).

Goodman, in attempting to appease feminists and other politically correct elements, may reveal some stories, and some trivia, about Scottsboro, but by juggling the chronology and evading crucial themes, Goodman has lost many of the important lessons of Scottsboro.

Ingalls concludes, “Other historians would do well to consider Goodman’s study as a model for how to construct their own stories about the past.” I view Goodman’s book as a model of evasion about the past to appease the politically correct of the present-a model to avoid.

Hugh Murray

Milwaukee, WI

In reply, Ingalls offered one sentence that one might characterize as snide, if not insulting.